human traffickingFeatures

Lawyers join renewed fight for free press

HRNJ’s Catherine Anite

Until now suppression of freedom of the media and as well as for expression in Uganda has been largely viewed as a problem for journalists.

“During the recent media siege, ordinary Ugandans simply kept quiet and all you could hear were muted views from people saying eh Museveni is powerful,” said Haruna Kanaabi, the President of the Eastern Africa Media Institute, while referring to the government’s latest ten-day closure of Red Pepper and Monitor Publications as well as its affiliated radio stations.

Indeed, except for a few activists from the civil society who joined journalists to protest the unlawful closure of the two publications, it was business as usual for most people in Kampala and other parts of the country.

But as Kanaabi noted, Ugandans are yet to understand that a free press is in their best interest because it allows them to express their views freely but also get informed about things that concern them.

“It was not like in Germany in 1950s where the closure of a single town newspaper got almost the whole population in that town to storm the street in protest,” adds Kanaabi.

However, the launch this week of a combined new effort by lawyers and journalists to fight the Uganda government’s growing suppression of freedom of the press and freedom of expression has been welcomed as a vital step to safeguarding Uganda’s democracy.

Code-named the new Partnership for a Free Press, lawyers under the Centre for Public Interest Law (CEPIL) a newly founded legal advocacy group have joined the Human Rights Network for Journalists (HRNJ) and the Eastern Africa Media Institute (EAMI) to challenge what many democracy activists regard as unacceptable Ugandan laws that violate internationally observed standards on freedoms of the press and of expression.

Leaders of the three bodies met with practicing human rights lawyers, law professors from Makerere University and media editors at Metropole Hotel in Kampala to layout their plans and build support for the initiative.

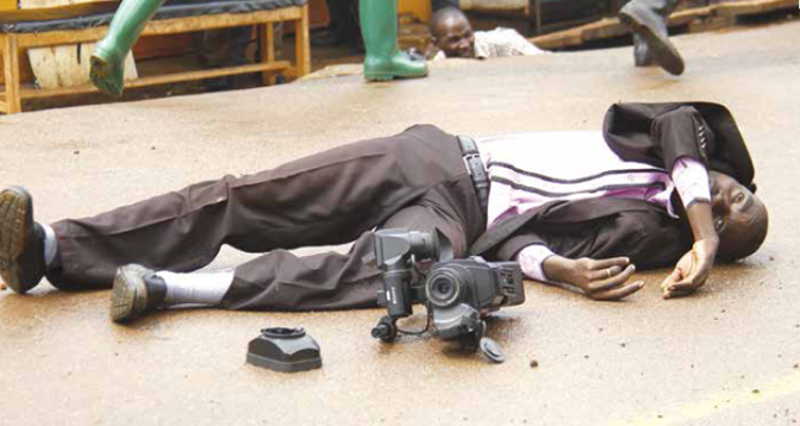

CEPIL’s Executive Director Francis Gimara, argued: “Ugandan journalists, despite a relatively free operating environment compared to many other countries in the region, still face considerable challenges in terms of police brutality, legal harassment, state interference in media houses and other abuses of freedom of the press and the media.”

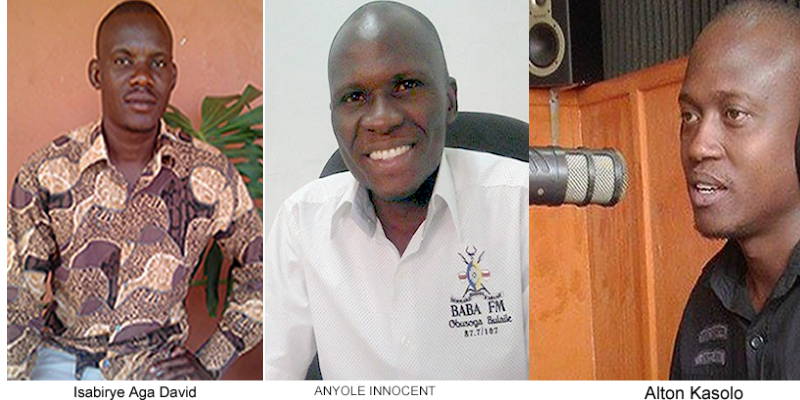

Catherine Anite, the head of the legal affairs at HRNJ noted that the coalition noted that their priority actions will involve carrying out advocacy on laws that impede on freedom of expression as well as freedom of the media.

Anite stresses that freedom of speech and freedom of the media are essential or fundamental to the attainment of other human rights such as the right to food, housing, a safe environment.

“If you cannot speak, you may not be able to eat,” says Anite.

Besides advocacy, the coalition intends to petition the constitutional court with the view to repealing a number of provisions that, according to Anite; “Do not facilitate the work of media and trample on the rights of journalists and the general public. We need to understand that freedom of expression is not a preserve of journalists.”

“When we bring these constitutional petitions, we are not only targeting journalists, we are targeting the country at large,” she adds.

Anite cited the Press and Journalists Act of 2002 as an attempt to stifle freedom of the media through its provisions that strictly define who a journalist is as well as requiring them to register and possess a practising certificate.

Anite argues that the requirement by the Press and Journalist Act that a journalist must have a degree, goes against globally recognised standards that consider journalism as a practice that is guided more by codes of ethics other than academic qualifications.

“This law can be used to target specific journalists through denial of certificates. We want an environment where journalists are able to operate freely,” said Anite.

Anite adds that the same law threatens access to information by media by forcing journalists to reveal their sources.

“By requiring journalists to reveal their sources, you’re putting the people who give them information in danger. For example, events like those that happened during the media siege when the police tried to force journalists to reveal the source of their letter, have serious consequences of keeping society at bay. They are in constant fear of facing criminal charges especially if they are civil servants or work in security institutions,” Anite adds.

“The irony is that we have a constitution which is seen as one of the most progressive on this continent. We have also signed as a country to highly regarded international conventions which protect civil and human rights and yet we are increasingly adopting very retrogressive laws is a disconnect.

“As citizens, we have to put pressure on our government to ask why they are doing the opposite,” said Anite.

Anite also cited the recently passed Uganda Communications Act 2013, as another retrogressive law because it gives too much authority to the Minister of Information Communications Technology in making policies, financial matters of the commission which is described by the same act as independent.

Over the past five years, the NRM government has also enacted laws that restrict freedom of the media. These include the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2010 which provides for a death penalty to anyone including a journalist who withholds information on any group which the government considers as a terrorist group.

The new found partnership for a free press however comes in the wake of several such initiatives by journalists to try to stop the government from passing laws considered unfriendly to the media and the press but have faltered.

Two years ago, despite massive lobbying of journalists and law-makers to strip the minister of excessive powers as enshrined in the Uganda Communications Act 2013, the bill was passed almost unchanged by the Ugandan Parliament.

But while the partnership from lawyers has been lauded as a sign of growing concern for concerted effort, the coalition faces serious challenges including a judicial system which is considered to be full of cadre judges that always make judgements in favour of the government.

Comments